InfancIa Under Siege – Impact of Unitary Coercive Measures on the Human Rights of Children and Adolescents. The case of Venezuela 2015-2019

by Anahi Arizmendi

Prologue

Introduction

Chapter 1 Unilateral Coercive Measures: A Threat to the Right to Development

Chapter 2 From Subjects with Rights to Sanctioned Subjects

Chapter 3 Coercive Measures and Unconventional Warfare

Chapter 4 Year 2019: Siege, Asphyxiation and Resistance

Chapter 5 Under Fire

1- Right to Food

2- Right to Health

3. Sexual and Reproductive Rights

4. Right to Education, Sport and Culture

5. Access to Public Services

6. Right to Housing

Conclusion

References

Index of Figures and Table

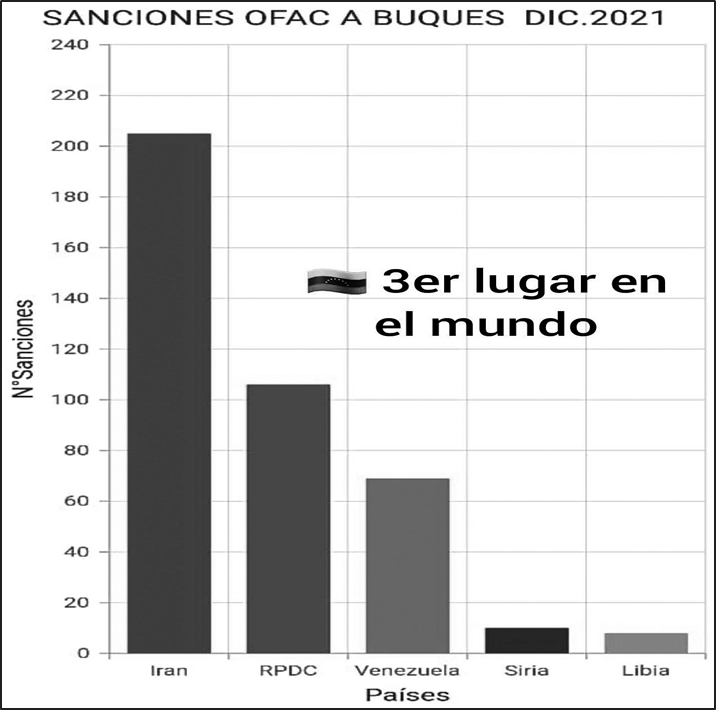

Figure No. 1 OFAC Vessel Sanctions Dec 2021

Figure No. 2 OFAC Aircraft Sanctions Dec 2021

Figure No. 3 Venezuela: Foreign Exchange Income from Public Entities to the BCV (2005-Sep. 2020)

Figure No. 4 Economic Impact of the Blockade

Figure No. 5 Oil Production Drop Nov 2018-March 2019

Figure No. 6 U.S. Government Humanitarian Funding for the FY-2018-2019 Venezuela Regional Crisis Response

Figure No. 7 Undernourishment Prevalence Index (IPS) vs. Sanctions Imposed to Venezuela from 2014-2021

Figure No. 8 Drinking Water per Inhabitant (m3/person)

Table No. 1 Summary of U.S. Unilateral Coercive Measures Against Venezuela 2019

Introduction

With the approval by the U.S. Congress in 2014 of the Law for the Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society in Venezuela. Law 113-278 [1] and subsequently on March 8, 2015 Executive Order 13.692 [2] declaring a “national emergency” due to the “unusual and extraordinary” threat to national security and foreign policy caused by the situation in Venezuela, the government of Barak Obama defines the backbone of the relentless application of unilateral coercive measures against the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and a series of actions that have to be carried out with the objective to disrupt the internal order and the political destabilization of the country in order to bring about a change of government.

[1] Congress of the United States of America. (2014, December 08). Law for the Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society in Venezuela. Public Law No. 113-278. https://observatorio.gob.ve/document-Category/Laws

[2] United States. Executive Office of President Barack Obama. (2015, March, 08). Executive Order No. 13692 Blocking of Property and Suspension of Entry of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Venezuela. https://lavozdelderecho.com/index.php/docu/item/3019-documen-text-of-barack-obama-president-of-the-united states-against-Maduro Moros Nicolás

Since then, a combination of information, psychological, media campaigns and universal political, economic, legal and diplomatic coercive measures have been applied and promoted, which have intensified since 2017 and are rearticulated in 2019 in the context of the so-called “interim government”, as instruments for the articulation of a series of alliances of national and international interests concerning our natural resources and goods and assets abroad.

Consequently, in the presentation of his Annual Report to the National Assembly in January 2023, President Nicolás Maduro reported that since 2014, Venezuela stopped receiving 642 billion dollars in the national economy (GDP). [3]

[3] Annual Management Message by Citizen Nicolás Maduro Moros. 2023. https://www.asambleanacional.gob.ve/storage/documentos/ documents/annual-management-message-at-charge-of-the-citizen-nicolas-maduro-moros-constitutional-president-of-the-bolivarian-republic-of-venezuela-20230113234443.pdf

Losses that, according to the research of Fundalatin* advisor, economist Pasqualina Curcio,** [4] were equivalent to 16 months of national production in 2020, or to total annual imports for 15 years, or sufficient resources to import food and medicines for 45 years; or investment in health (public or private) for 29 years.

The effects of these measures would lead former United Nations Special Rapporteur Idriss Jazairy (2019) to reflect on the need to “express compassion for the suffering of the Venezuelan people by promoting, not cutting, access to food and medicine”. [5] The negative impact of UCMs in the field of human rights was corroborated by the United Nations Special Rapporteur to measure the Negative Impact of Coercive Measures in Venezuela, Alena Douhan (2021), who testified during her visit to the country, the brutality of this policy of imperial aggression. “The measures have exacerbated the pre-existing economic and human situation by impeding the generation of income and the use of resources for the development and maintenance of infrastructure and for social support programmes, which has a devastating effect on the entire population of Venezuela.” [6]

[4] Curcio, P. (2020, July, 11). Impact of the economic war in Venezuela. Correo del Orinoco. http://www.correodelorinoco.gob.ve/mpacto-de-laguerra-economica-envenezuela-actualiza-do/

[5] Jazairy, Idris. (2019, January, 31). Sanctions on Venezuela violate the human rights of innocent people. http://www.minci.gob.ve/idriss-jazairy-sanciones-a-venezuela-aten-so-against-the-human-rights-of-innocent-people/

[6] United Nations. Human Rights Council. (2021). Report on the Negative Impact of Unilateral Coercive Measures on the Enjoyment of Human Rights [presented by Douhan. Alena, Special Rapporteur] https://www.ohchr.org/es/special-procedures/ sr-unilateral-coercive-measures

[*] The Latin American Foundation for Human Rights and Social Development, Fundalatin, is a civil, Christian-ecumenical organization, created in 1978, inspired by Liberation Theology and Bolivarian Thought, which focuses its attention on the oppressed sectors of Latin America.

[**] Pasqualina Curcio: Venezuelan economist. Professor at the Simón Bolívar University (USB), with Postdoctoral Studies in Security and Defense of the Nation from the Bolivarian Military University of Venezuela (2019). Author of the books The Visible Hand of the Market. Economic war in Venezuela; Hyperinflation. Imperial weapon; among others.

As an expression of this debate during the 52nd ordinary session of the Human Rights Council (27 February – 4 April 2023), the resolution presented by the Non-Aligned Movement condemning the unilateral and continuous application and execution of coercive measures as an instrument of pressure against any country was adopted by a majority. in particular against the least developed and developing countries, and recognizes the disproportionate impact on people in situations of maximum vulnerability. The resolution reaffirms that each State has full sovereignty over all its wealth, natural resources and economic activity and freely exercises that sovereignty in accordance with General Assembly Resolution 1803 adopted in 1962. [7]

[7] UN Human Rights Council adopts resolution condemning the use of coercive measures. (2023, April 03). Venezuelan News Agency. http://www.avn.info.ve/ node/524538

Actions such as the UCM strike at the social state, the rule of law and justice and the welfare policies of the Venezuelan state. The so-called sanctions, which are described by the United Nations as actions that constitute crimes against humanity, systematically disrupt the all-around development of children and adolescents and consequently the family and community fabric.

In fact, the Convention on the Rights of the Child establishes “the right to an adequate standard of living” as a fundamental right (Article 27) also enshrined in national legislation, in the Organic Law for the Protection of Children and Adolescents (Ley Orgánica para la Proteccion De Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes) in Article 30.

In the case of Venezuela, the application of these measures is part of a combined strategy that has included terrorist and destabilization actions, such as calls for violent street closures (guarimbas), burning of public transport facilities and attacks on educational and welfare centers, violating the rights to life, health, education, food, free movement, etc. recreation, among others, for children and adolescents.

In this policy to force regime change in Venezuela and seize resources such as oil, gas, gold, and chemical and mineral elements used to manufacture technological products (rare earths), the U.S. government promotes and finances a large international conspiracy, supporting the legitimization of an “interim government” in 2019 and applying new executive orders.

To this end, two days after the self-proclamation in a Caracas square of Deputy Juan Guaidó as “President of Venezuela”, former President of the United States Donald Trump signed on January 25, 2019, Executive Order 13857 [8] which establishes the modification of the paragraphs of each Executive Order since 2015. It used the term “Government of Venezuela” to adapt these decrees to the recognition of the “interim government” by the United States. That same year, on August 5, Trump endorsed Executive Order 13884 [9] that froze all the assets of the government of Venezuela in U.S. territory, in the face of the alleged usurpation of power by President Nicolás Maduro.

[8] Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory (2019, January 25). Executive Order 13857. On the adoption of additional measures to address the national emergency with respect to Venezuela. https:// observatorio.gob.ve/document/orden-ejecutiva-13857-del-25-de-enero-de-2019-imposicion- of-additional-measures-to-face-the-national-emergency-with-respecting-venezuela/

[9] U.S. Federal Government l (2019, August 05). Executive Order 13884. Blockade of the property of the Government of Venezuela. Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory. https://observatorio.gob.ve/document/orden-ejecutiva-13884-del-05-de-agosto-de-2019-bloqueo-de-la- property-of-the-government-of-venezuela/

With the recognition and support of an administration tailored to its needs, and with a total of 927 unilateral coercive measures as of March 2023, the government of Washington intensified the economic embargo of Venezuelan assets and goods abroad, the freezing of the country’s financial resources and the increase of coercive measures and prohibitions against companies and institutions that wanted to establish transactions with the constitutional government of President Nicolás Maduro, affecting social investment and policies for the integral protection of Venezuelan children.

This research aims to evaluate the cumulative impact of these inhumane measures promoted and financed by the government of the United States and allied countries until 2019, on the right to an adequate standard of living of children and adolescents, as part of the unconventional weapons of war against Venezuela, and of which they are their main victims.

Chapter 1 Unilateral Coercive Measures: A Threat to the Right to Development

The UN defines Unilateral Coercive Measures as “economic measures taken by one State to compel another State to modify its policy.” (UN, 2012, p.3). They can be legally enforced by the United Nations Security Council, as well as regional bodies such as the European Union and the Organization of American States. However, the Organization’s Human Rights Council (2012) questions the legal nature of these measures with negative repercussions on the enjoyment of human rights.

The Thematic Study of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Effect of Unilateral Coercive Measures on the Enjoyment of Human Rights, with Recommendations on Ways and Means to End Such Measures (2022), recognizes that:

The term “unilateral coercive measures” is difficult to define. This term usually refers to economic measures taken by one State to force another State to change its policy. The most widespread forms of economic pressure are trade sanctions, which take the form of embargoes and/or boycotts and the interruption of financial flows and investment flows between the country imposing the measure and the country to which the measure is applied. Embargoes are often understood as trade sanctions aimed at preventing exports to the country to which they are imposed, while boycotts are measures aimed at rejecting imports from the target country. However, the combination of import and export restrictions is often also referred to as a trade embargo (…) it follows from this definition that unilateral coercive measures, regardless of their legality under a particular body of rules of international law, can have a variety of negative repercussions on human rights (p. 3). [1]

[1] United Nations. (2012 January, 11). A/HRC/19/33 https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/ Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session19/A-HRC-19-33_sp.pdf

The negative impact of this type of instrument is admitted in October 2014 in the Resolution approved by the Human Rights Council 27/21 Human Rights and Unilateral Coercive Measures [2], which urges all States to:

… to refrain, maintain or apply unilateral coercive measures contrary to international law, international humanitarian law, the Charter of the United Nations and the norms and principles governing peaceful relations between States, in particular coercive measures with extraterritorial effects, which create obstacles to trade relations between States, thereby impeding the full realization of the rights set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments, in particular the right of individuals and peoples to development… (p. 2)

[2] United Nations. Human Rights Council (2014, October 3). Resolution A/HRC/RES/27/21. Human rights and unilateral coercive measures. https://www.ohchr.org/es/ special-procedures/sr-unilateral-coercive-measures/resolutions-and-decisions-mandate

The Council expresses its grave concern regarding the situation of children and women in some countries as they are adversely affected by the application of unilateral coercive measures contrary to international law and the Charter, that:

… create obstacles to trade relations between States, impede the full effectiveness of social and economic development and undermine the well-being of the population of the countries concerned, with particular consequences for women, children, including adolescents, the elderly and persons with disabilities… (p. 4).

In August 2015, in the Report of the Special Rapporteur on the negative repercussions of Unilateral Coercive Measures on the enjoyment of Human Rights, Idriss Jazairy,[3] referring to Human Rights Council Resolution 27/21, she states that “it can be inferred that the unilateral coercive measures are measures that include, but are not limited to, economic and political measures imposed by States or groups of States to coerce another State in order to obtain from it the subordination of the exercise of its sovereign rights and to bring about some concrete change in its policy” (p.5).

[3] United Nations. Human Rights Council. (2015, August, 10). Annual Report [submitted by Idriss,Jazairy, Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights]. 30th Session. A/HRC/30/45. https://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page?=- search&docid=565ff2df4&skip=0&query=Idris% 20jazairy

Point 16 of that report states:

Unilateral coercive measures may be general or specific. The latter are also known as “selective” measures. They owe this epithet to the assertion that they minimize collateral damage, particularly in terms of avoiding jeopardizing the enjoyment of human rights by the poorest and most vulnerable groups in the society of the country targeted by the measures. The former are measures aimed at the entire economy or financial system of a country. They tend to be indiscriminate and thus have a negative impact on the human rights of the poorest and most vulnerable sectors of society in the target country. Its effectiveness is measured in the light of its ability to impose far-reaching policy changes or create sufficient economic hardship in the recipient country to incite the population to rebel against its political leadership. ‘Selective’ coercive measures, on the other hand, may target certain sectors of a country’s economic activity or be broader in scope but specific to a circumscribed part of the territory. Its effect may be to destabilize a particular sector of production or a certain geographical area. The right to work and to have a decent standard of living of the people who generate their income in that sector or region may be compromised. In theory, however, the negative impact of human rights measures is likely to be more limited in both cases than in the case of general coercive measures aimed at a country as a whole. In practice, it can be difficult to distinguish between some unilateral ‘selective’ coercive measures and general ones… Jazairy (2015).

Likewise, a constant in the application of unilateral coercive measures in our times is identified, such as that “most of the current unilateral coercive measures have been imposed by developed countries on developing countries at a high cost in terms of the human rights of the poorest and most vulnerable groups. The tendencies of the observed trends do not show that the advanced countries are reluctant to resort to unilateral coercive measures, but quite the contrary.” (Ibid., n.d.).

Regarding the different concepts, Giménez and Alson (2021) [4] warn that a distinction must be made:

… between the sanctions themselves, known in the multilateral sphere as Unilateral Coercive Measures (UCMs), in the sense that they are imposed by one State on another State without the approval of the United Nations, and in particular the Security Council, and, on the other hand, the so-called Punitive and/or Restrictive Measures, which are complementary to them and often have the same or even worse results, such as the aforementioned SDN list.

Refers to the list of Specially Designated Nationals (“SDNs”). Those against whom the Department of the Treasury may take “preventive measures” to prevent them from doing business with nationals of the United States and companies or branches located in that country, through their financial institutions and using their legal currency, by virtue of a suspicious situation in the field of drug trafficking, terrorism and its financing, human trafficking, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, malicious computer attacks on U.S. cybersecurity, among other reasons.

[4] Giménez P, & Alson, A. (2021). Damage to the Venezuelan economy as a result of the imposition of unilateral coercive measures 2015-2021. Souths. https://sures.org.ve/economia-venezolana-medi- unilateral-coercive-das/

Jazairy stresses in his report that “whether general or ‘targeted’, it is difficult to reconcile unilateral coercive measures with the Declaration on the Right to Development, in particular its article 3, which stipulates that “States have a duty to cooperate with each other in achieving development and removing obstacles to development”.

The Declaration of the United Nations General Assembly (Resolution 41/128. Dec, 1986) defines the right to development in Article 1 as:

… an inalienable human right by virtue of which every human being and all peoples are entitled to participate in, contribute to and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development in which all fundamental human rights and freedoms can be fully realized. [5]

[5] United Nations. Human rights. (1986, December, 04). Declaration on the right to development. (Resolution 41/128) https://www.ohchr.org/es/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/ declaration-right-development

The right to survival and development is enshrined in Articles 6 and 27 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) which provide that “States Parties shall ensure to the maximum extent possible the survival and development of the child” (Art. 6) and “States Parties recognize the right of every child to a standard of living adequate for his or her physical development, mental, spiritual, moral, and social.” (Art. 27)

The impact of UCMs on children’s rights is of such magnitude that a UNICEF working group’s analysis, “Sanctions and their impact on children”, by Pelter, Z., Teixeira, C., Moret, E. (2022) concludes by recommending the urgency of concerted action to renew sanctions policies to ensure that these mechanisms meet their explicit objectives, rather than harming children”. [6]

[6] Pelter, Z., Teixeira, C., and Moret. E. (2022). Sanctions and their impact on children. Discussion Document.|An analysis of the harm to which children are subjected in countries that have been severely sanctioned. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/es/informes/las-sancio-nes-and-their-repercussions-on-childhood

The researchers identify three main channels through which sanctions affect children and adolescents due to their effects:

a) Consumption: Countries subject to widespread sanctions often experience an increase in the price of goods, driven by limited imports and currency depreciation, resulting in a reduction in household purchasing power. These effects can be particularly severe in the case of the procurement of food and medicines, for which many countries depend on imports.

b) Labor markets and household incomes: Countries affected by sanctions are experiencing an increase in economic uncertainty, reduced demand for exports, and foreign capital flight, culminating in reduced business activity, declining wages and rising unemployment. Historical evidence suggests that, in some cases, women bear the brunt disproportionately. This puts additional pressure on households’ consumption of child-related goods and services, and encourages negative coping strategies, such as inadequate food, asset sales, child labor or school dropout.

(c) Provision of government services: Sanctions often reduce government revenues, either by restricting the export of state-owned natural resources or by hindering other taxable economic activities. This can lead to cuts in public spending on services for children, including health, education and social protection, and the collapse of crucial systems for social services (p.21).

This discussion paper by the Office of Global Policy and Perspective [Oficina de Políticas y Perspectiva Mundial] as an internal think tank of UNICEF, also describes the areas of health, water and sanitation, adequate and nutritious food, adequate standard of living, education and response to the Covid-19 pandemic, as those with the greatest negative impact as a result of unilateral coercive measures in the context of the deterioration of the rights of childhood.

The authors also argue that the number of sanctions being used simultaneously around the world has increased continuously since 1950:

… The United States has imposed sanctions regimes more frequently and for longer than any other country… Since 2016, the United States has significantly increased its use of sanctions. On average, the United States imposed sanctions on more than 1,000 entities or individuals each year from 2016 to 2020. (pp, 5-6).

The unilateral actions of the United States against Venezuela are framed by the confrontation between the Bolivarian project and the Monroe Doctrine.

Sovereignty and independence against subordination and imperialism are antagonistic projects that have clashed on various grounds. As early as the nineteenth century, the United States applied what could be assumed to be a precedent for unilateral coercive measures against the Bolivarian patriotic proposal, with the new “Neutrality Act”, approved by the U.S. Congress. on March 3, 1817, which established that any person discovered transporting arms to a South American state in favor of the patriots, would be punished with 10 years in prison and a fine of 10,000 dollars.

The refusal to sell arms to the Venezuelan patriots and the acceptance of Spain’s requests were, therefore, not a casual attitude of the US authorities. It was the result of an expansionist policy, which was in contradiction with the national independence movement of the Spanish colonies. The U.S. rulers aspired to succeed the Spaniards in colonial rule. (Linares & Gómez, 2021, p, 21).

Even though there are more than 30 countries in the world to which coercive measures are unilaterally applied, the Venezuelan case is one of a concentration of criminal fire: no less than 927 coercive measures against individuals, institutions, services and collectives during the period 2014 to 2022. (*CIIP, 2022, p.10) [7]

[7] International Center for Productive Investment. Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory. 2022, December, 12). The Numbers of the Blockade 2014-2022. Editorial Ministry of the People’s Power of Economy and Finance. Venezuela. https://observatorio.gob.ve/document/ the-numbers-of-the-blockade-2014-2022/

As part of Obama’s interventionist policies and the stage of what former President Trump defined as “maximum pressure” from 2017 to 2019, “of the total measures against Venezuela, eight out of ten correspond to direct sanctions (763), the rest are restrictive or punitive measures (164). Of these, 42% of the decisions and measures were directed against government agencies, 18.7% against the oil industry, 17% against the economy and finances of the Republic and 7% against the private sector.” (Ibid., pp.12 and 15)

Of the countries that have imposed the 763 direct sanctions or unilateral coercive measures, 483 correspond to the United States (57.4%), 6 out of 10 measures, Canada 108 (14.2%), Panama 70 (9.2%), Switzerland 56 (7.3%), European Union European 55 (7.2%), United Kingdom 36 (4.7%). Of these, 467 have been against individuals, 169 against companies, 69 against ships and 58 against aircraft. (Ibid., p.16).

As of December 2021, Venezuela ranked fifth in the world in company sanctions by the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), as well as third in ship sanctions, fifth in individual sanctions, and second in aircraft sanctions.

Figures 1 and 2 show the application of unilateral coercive measures against Venezuela from 2014 to Dec. 2021Source: Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory

Figure No 1.

Figure No 2.

Source: Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory

The impact of these measures on the Venezuelan Human Development Index and the Gross Domestic Product has been decisive. This is even more so when compared to the progress made until 2014 in public policies for the protection of children in the areas of food, education and housing, the year in which the United Nations gave the name “Hugo Chávez” to its Plan of Action for the Eradication of Hunger and Poverty.

In this context and to provide the Executive with a tool to confront the continuous aggression that these actions represent against the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, the Constituent Assembly approved the Anti-Blockade Constitutional Law for National Development and the Guarantee of Human Rights, (12/05/2020) Extraordinary Official Gazette of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela N° 6,583. This legislative instrument defines unilateral coercive measures as:

… the use of economic, trade or other measures taken by a State, group of States or international organizations acting unilaterally to force a change in the policy of another State or to pressure individuals, groups or entities of the selected States to influence a course of action, without the authorization of the Security Council of the United Nations Organization (Art. 4).

It also establishes as Other restrictive or punitive measures: “any act or omission, whether or not connected with a unilateral coercive measure”. (Ibid.)

The [Anti-Blockade] Law responds to a strategic need to reduce the negative effects of sanctions and relaunch a self-sustaining economic model, based on the productive economy, […] and has made it possible to create and strengthen mechanisms that reinforce public policies, such as the International Center for Productive Investment, which stimulates internal economic activity and external productive alliances. that seek to promote national development through the promotion of investments in strategic sectors and new actors in commercial and industrial activities and, on the other hand, the Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory, as a scientific body for the generation of pertinent and relevant knowledge, in order to disseminate the issues, data and harmful effects of unilateral coercive measures and other restrictive or punitive measures in a pedagogical way, for the benefit of collective knowledge and, in particular, for the benefit of the Venezuelan people. (Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory 2022). [8]

[8] Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory (2022). https://observatorio.gob.ve/leyconstitucio-anti-blockade-nal-two-year-from-your-approval/

The law has had a positive impact on the enjoyment of the rights of children and adolescents by directing resources towards:

1. Develop compensatory systems for workers’ wages or real incomes:

2. Financing the functioning of the social protection system and the realization of human rights

3. Recover the capacity to provide quality public services

4. Boost the national productive capacity, especially of the strategic industries and import substitution and

5. Recover, maintain and expand public infrastructure. However, unilateral coercive measures have jeopardized the right to development of the Venezuelan population and, in particular, the human rights of children and adolescents.

Even so, the UCMs have put at risk the right to development of the Venezuelan population and in particular the human rights of children and adolescents.